You just spent a grand and waited a year to get your new silencer (although now you might just wait a mere week) and it’s finally “go time.” The shot is surprisingly louder than you expected, and the rifle stings your hand like a broken baseball bat. Your spotter calls a miss and when you look down, your new silencer is a twisted-up mess. Or, your spotter keeps calling misses. Baffled, you check and there is copper all over the edge of the end cap of the silencer.

Bullet strikes are a royal pain. If you’re lucky, it’s the second scenario, and your silencer is still intact. Either way, you have learned a hard truth that installation is critical with a silencer. As a rule, the hole through the device is not a lot larger than the bullet, so things must be aligned correctly.

Before we get too far into this and to avoid all the e-mails, phone calls, social media posts and other criticisms, let me explain. I call it a silencer. Suppressor works, too, and is in more common use today. Hiram Maxim used “silencer” in his original patent so, in tribute to the guy who invented the thing—and because that’s the term the NFA uses to describe them—I use it, too. In other parts of the world, it’s a moderator, or if you are one of the cool kids, you call it a can. Call it anything you want, just don’t call the editor.

We DIY guys have been putting stuff on the end of our rifle barrels for a long time—flash hiders and muzzle brakes mostly—and it’s all been good. Then silencers became affordable, and more recently the wait time for approval from “the King” has gotten much shorter. Their popularity has soared, and so has the potential for problems.

Like most things in life, there is a right way and a wrong way to do this. Just because you have been getting away with the wrong way does not make it right. It’s a given that sooner or later, your luck will run out.

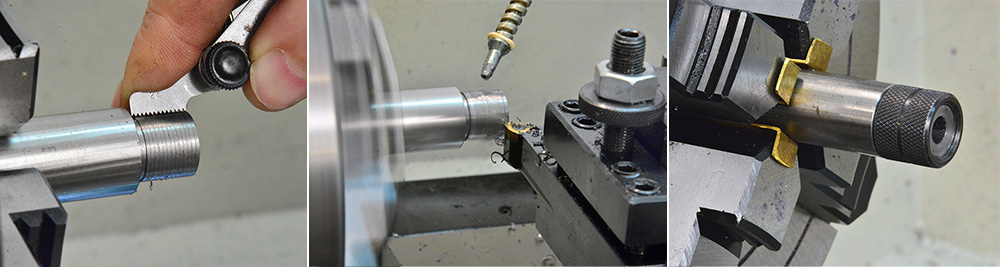

This Silencer Central suppressor uses a QD attachment via a muzzle brake, which can be used on its own in addition to being a silencer mount. The brake must be timed, and the use of a shim washer allows it to stop in the correct location • To help prevent costly baffle strikes, a guide rod is an invaluable tool • Clearance around the guide rod shows proper alignment.

When installing a silencer, or any muzzle device for that matter, it’s important to do it on a barrel with a threaded muzzle and a good, square shoulder to butt against. In these times of computer-controlled machining, most newer guns usually have muzzle threads that are precisely cut. Be careful about installing anything on military-surplus rifles, as the threads may or may not be aligned correctly. When in doubt, have a gunsmith take a look.

For those guns still unsullied, threading a barrel is not difficult for any competent machinist or gunsmith. I have detailed instructions on how to do it in my book, “Gunsmithing Modern Firearms.” If you have a lathe and some experience, have at it. If not, take it to a gunsmith or send it to Silencer Central.

Threading a barrel requires access to a lathe, though companies like Silencer Central offer this service • The use of cutting oil is essential to avoid damaging the barrel • A protector keeps threads safe.

With any muzzle-device installation, the barrel must be held firmly. Do not hold the gun by its action, stock, forearm or anything else that’s not the barrel. You will be twisting and torquing against things not designed for twisting and torquing, and that can lead to problems. Hold the barrel, not what is attached to the barrel.

It’s also a good idea to protect the barrel against marring with brown wrapping paper, sheetrock tape or even a few coats of masking tape. Clamp tight so nothing turns inside the vise and it’s all good.

There are several different aluminum barrel clamps designed to be used in a bench vise that work well. I bought a set that was specific to AR-type rifles some years ago and they were great. I just wish I could find them. They ran away from my shop and haven’t been seen in years. I am going to order a new set, which guarantees that the missing ones will show up soon after.

If you are setting up shop, you will need a bench-mounted vise for working on guns. Consider the Real Avid Master Gun Vise. This has interchangeable jaws, some of which are designed to hold round parts, including barrels. I have found this to be a useful tool for a lot of gun-tinkering chores.

If you already have a vise, you can buy soft jaws that will work pretty well. Hard-plastic or nylon are easy on the metal finish. Get one with a large V-groove to hold the round barrel better.

The two common muzzle threads used the most today are 1/2×28 and 5/8×24 tpi. The first number is the thread diameter. The second is the number of threads per inch. There are others, but these two are the most popular. You must match these threads with the female thread on your muzzle device.

The three muzzle devices in common use are the flash hider, compensator/brake and silencer. While they all attach at the muzzle, installing each is a bit different.

Soft jaws for a bench vise are inexpensive and useful for working on guns, but they can’t hold much torque • Homemade wooden barrel-vise blocks are an inexpensive option for installing muzzle devices • Checking measurements at all stages is vital, as clearances can be quite small • The use of a torque wrench makes most installations significantly easier. They are vital tools for anyone working on guns and usually last forever.

For a flash hider, it’s usually a matter of screwing it on tight. Some may have a top and a bottom, so you will need to orient it correctly on the barrel. The most common way is to use a crush washer. This is a cone-shaped washer that goes between the flash hider and the shoulder on the barrel with the wider, flat end to the barrel and the tapered end toward the muzzle device. A little anti-seize lubrication on both ends of the washer is a good idea.

Anti-seize is designed to allow metal parts to move against each other without galling or friction. It’s sold under several brand names and is easy to recognize. It’s a silver-colored grease that instantly coats your hands, face and tools as soon as it’s opened. I simply walk by an open tube sitting on my bench and my hands turn silver. Great stuff, though, for its intended use.

Using a wrench on the flats of the flash hider, turn until it’s tight and aligned—hand tight and at least half a revolution further with the wrench. Never reuse a crush washer; always replace it with a new one. Never use a crush washer when installing anything that has baffles or a tight fit for the bullet to pass through. That includes most brakes and all silencers.

A muzzle brake is slightly different than a flash hider or silencer, as it needs to be timed or “clocked” for the best results. Usually that means level or slightly cocked to the right for a right-handed shooter. Shooting the gun will tell if this is correct, and it might take a little tweak one way or the other to fine-tune the brake.

Some brakes have a jam nut to lock them to the barrel. A separate nut is threaded in on a threaded stem and can move independent of the brake. The brake is turned into place and timed and then the jam nut is backed against the shoulder to lock everything in place. This takes two wrenches—one to hold the device and another to tighten the jam nut. A little Blue 242 Loctite will keep it in place, or the more permanent Red 262 if you are feeling froggy.

Many brakes double as an attachment point for a silencer. You can use the gun with the brake only or install the silencer. If you are going to use the brake as an attachment for a silencer and it’s not timed correctly when tight to the barrel shoulder, then the only acceptable option is to use a shim to adjust the timing. This is also the best option for most stand-alone brake installations that do not have a jam nut.

The shims are usually sold in packs with washers of various thickness. These are available from Precision Armament for both 1/2- and 5/8-inch threads. One 18-washer package will usually do up to nine installs before you need replacement washers. It is recommended that only one washer be used in the installation. The trick is to find the thickness that allows the brake to be timed correctly when it is tight.

Install the washer and hand tighten the brake until it stops. It should stop a little short of where you want it, something like 10 to 30 degrees. This is so when you torque it tight with a wrench to a minimum of 20 ft.-lbs., the brake is correctly aligned. If not, a thicker or thinner shim is needed. Again, anti-seize grease is recommended.

As a guide, with a 1/2×28 thread, each full rotation will move the device in or out .0357 inch (1 divided by 28). For those using 5/8×24 thread, each full rotation moves the device in or out .04167 inch. So, if you are installing on a 5/8×24 thread and need about half a rotation more to regulate the brake, remove .020-inch in thickness in the shims. The key is you want the muzzle brake tight. So, hand tighten until it’s around a quarter turn off and then finish with a wrench.

Some manufacturers recommend that a brake be installed with a thread locker. Opinions on this vary, and some say no thread locker is needed. Other than the difficulty in later removal, I don’t think it’s ever a mistake. Due to the heat involved when used with a silencer, Rocksett is recommended here over other, heat-sensitive thread lockers. If the brake needs to be removed later for any reason, soaking it in hot water will release the Rocksett.

A silencer may use a quick-detach device that may or may not also be a brake. It may be a direct screw on the barrel threads or use a hub with a thread that will allow a direct screw on the barrel threads. As they do not need to be timed, a direct screw-on silencer can be installed without any worry about shims or washers.

Blue Loctite is removable, and is a good option for use with muzzle-device installations • Installing a brake using a lock nut will require two wrenches • Muzzle brakes come in a variety of styles and ways of directing gases to reduce muzzle rise and felt recoil. Some also double as suppressor mounts.

As many silencers are made from different metal than the threads on the barrel or attachment device, anti-seize lubrication is indicated on the threads to prevent galling. Also, dissimilar metals can experience electrolysis-caused corrosion over time, so it’s important to not store long term with the silencer installed.

Tighten the silencer to a snug, hand tight. Check every five or so shots to make sure it does not loosen. Do not overtighten using a wrench or a Wookie-size guy on testosterone supplements, to hand tighten. This can damage the silencer.

In my former life, I was a bit of a gearhead and spent some years as a mechanic for cars, motorcycles and manufacturing machinery. I vividly recall the old auto mechanics giving me a hard time when I bought one of the newfangled torque wrenches. (I might note that I bought a good one and now half a century later I am still using it when installing rifle barrels. Nobody ever regretted buying quality tools. As they say, “Buy once, cry once.”) All those guys spouted their reasons why you didn’t need a torque wrench, most centered on their unbridled commitment to never learning anything new.

It’s the same with working on guns. In fact, it’s even worse with the internet spreading the hate. I see time and time again how you don’t need this or that tool. “Just shoot it!” is one common refrain. In many circumstances, that less than scientific approach can lead to big problems.

One example is using a guide rod to install a suppressor. The tolerances are pretty close with many silencers, and even a small misalignment can destroy your new can and cost you a grand or more. Half the posts are something like, “I have installed [insert number] and never had a problem! You don’t need a guide rod.” Right up until you do.

A guide rod is a precision steel rod that is specific to each bore diameter. The rod is inserted into the bore and will tell at a glance if the silencer is lined up correctly. If the rod is centered in the silencer and is not contacting it anywhere, then everything is correct. If the guide rod does contact the silencer, do not shoot the gun. Have the threads realigned by a good gunsmith or send the gun back to the factory for repair or replacement of the barrel. Or, change to a silencer with a larger-diameter hole. The rods are not cheap, but neither is a new silencer. If you are going to mess with silencers much, it’s a good investment to have a correct guide rod in your shop. Owning the right tool for the job is never a mistake. My guide rods are from Griffin Armament. Beware of internet suggestions about making your own from drill rod. The tolerances are just not tight enough to work correctly.

A much less reliable option is to remove the bolt and look down the bore with the silencer installed. If you don’t see any shadowing and can’t see any part of the silencer or mount, it might be fine. That’s how the internet wizards do it. (As well as some experienced gunsmiths.) Just remember, you are mounting your muzzle device that will have pieces of metal flying through it at 3,000 fps or faster.

Life has less drama if you do things right.

Read the full article here